The White Mountain Monastery, part of Russia’s tragic past and a testament to the resilience of a people

On Sunday the members of our expedition to locate the remains of the Grand Duke Mikhail Romanov were taken on a field trip by our Russian hosts to the Belaya Gora (for White Mountain) monastery. Located on a high hill about 100 kilometers from Perm, the monastery is both a reminder of Russia’s tragic past, as well as a metaphor for the resilience of the Russian people and their faith.

Inside the White Mountain Monastery church

The monastery is dominated by a large, beautiful white church with gold domes topped by golden crosses. Inside the church, with its high, arcing ceiling, the walls are covered with classical Russian Orthodox paintings and icons of saints and religious scenes. Here, too, gold is the dominant color from the icons themselves (the creators actually use gold dust, which they sprinkle over glue) to the painting frames to the crystal chandeliers.

From a distance as one approaches the monastery on a two-lane road, the church appears as a gleaming white edifice, its domes reflecting the sun under clear blue skies. However, on closer inspection the white paint has faded and the façade has worn away in spots. Some of the smaller domes await burnishing as workers labor to repair the damage and replace the paint.

The living quarters for the monks at the White Mountain monastery

Next to the church stands a large brick building that looks like an old dormitory and, indeed, once housed some four hundred monks who lived on the grounds. It, too, is being renovated so that it may again serve that purpose though there are many fewer monks.

A cross commemorating the survival of heir to the Russian throne, Nicholas II, after an 1891 assassination attempt in Japan

An enormous cross rises from the ground overlooking the valley below. It’s a replacement for a smaller wooden version that once stood there commemorating the survival of the young heir to the Russian throne, Nicholas II, after he was attacked by a sword-wielding assassin in Japan in 1891. Twenty-seven years later, Tsar Nicholas, his wife and empress, Alexandra, their four daughters and son, as well as servants, would be murdered by Bolsheviks in the basement of the Ipatiev house in Ykaterinburg some 600 kilometers to the southeast on the other side of the Urals.

Although the hill is maybe only a thousand feet tops in elevation, the view of the valley that surrounds it on all sides is breathtaking, particularly looking east towards the

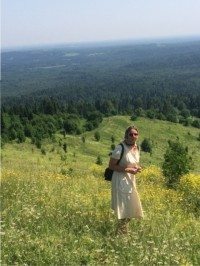

One of our Russian friends and team member, Aleksandra “Sasha” Bukrina in a field below the monastery looking east towards the Urals.

Urals. The land is dotted with small farms and villages, but dominated by fields of wildflowers and an immense conifer and birch forest that stretches off to the horizon as far as one can see. I can’t help but hum “Somewhere My Love (Lara’s Theme)” from the movie version of Boris Pasternak’s classic novel set during the Russian revolution and civil war, Dr. Zhivago (written by the way in Perm).

However, there was nothing beautiful about the Russian revolution and civil war. This is a land steeped in bloody history. Here the Red and White armies swept back and forth across the region bringing death and terror to millions. In particular, the Bolsheviks and their heirs, the Communist Party, particularly had it in for the Russian Orthodox Church, its priests and its adherents. That virulence would be visited upon the White Mountain monastery.

Geophysicist Clark Davenport, a member of NecroSearch International and part of the Mikhail Romanov search team, examines the marks left in the church wall where the monks were shot

One day in 1918, the local Bolsheviks arrived at the monastery and demanded that the leader go with them to “attend a meeting.” Instead, he was taken by carriage to the valley below, shot and thrown in the Kama River. The killers, however, weren’t through with the monastery. They returned and proceeded to kill the monks living there. There is some discrepancy about the number of monks, and what happened to all of them. Our guides told us all four hundred were killed; other accounts say forty with some deported. What is certain is that some were lined up against the church walls and shot. It was sobering to touch the bullet holes still evident in the walls. An account also claims that the killers buried others alive in a mass grave and that according to villagers at the time, the ground above the grave moved for several days as the monks slowly suffocated. The church was also burned several times though not completely destroyed.

While perhaps not as dramatic, the terror perpetrated on the inhabitants of the White Mountain monastery would be repeated throughout Russia. Priests and monks dragged from their quarters and murdered; priceless works of art stolen or vandalized. Even after the civil war was won by the Reds, the Soviet Union established, and the murders and attacks no longer state sanctioned, it remained dangerous to belong to the church.

This was the monastery in ruins and prior to the current renovations

Few populations have suffered as much as the Russians since the beginning of the 20th century. Between the World War I, the revolution and civil war, the Red Terror, the Great Patriotic War (World War II), and the suffering under the Soviet Union, hundreds of millions have died violently, starved to death, or succumbed to diseases, been displaced and imprisoned for political or “subversive” reasons.

Yet, most of the Russians I’ve had the pleasure of associating with on the two expeditions I’ve been on, while perhaps fatalistic in their outlook, are also life-affirming and warm-hearted. They tend to take pleasure in small things, in family and friends, in walks in their parks and picnics. Those old enough to remember the days before the disintegration of the Soviet Union talk about the joy of rediscovering their history, much of it kept from them or lied about by the former government, and their culture.

Having survived the unimaginable, the church, too, is experiencing a reinvigoration as more of the population embraces their past. Among our hosts were former Young Pioneers, the youth organization of the Communist Party during the Soviet regime. When “perestroika,” a political movement for reform, and “glasnost,” meaning “openness,” swept the country in the 1980s, they learned that much of what they’d been taught about their history and the church wasn’t true. And they found meaning in embracing the faith of their ancestors, which they describe in terms of love for life and each other, as well as a spiritual awakening and personal growth.

Those helping us with the search for the Grand Duke Mikhail aren’t just interested in the historical importance or to bring a resolution to an old crime. The Romanovs are considered martyred saints in Russia by the church, and their part in the search for Mikhail is also a religious one. Our friends want Mikhail found so that he, as with the members of the royal family, can be buried as befitting their role in Russian history and the church.

Maybe it would be different in Moscow or St. Petersburg where the emphasis is on modernity. But in the Perm region, the Russian Orthodox Church isn’t just their religion, it’s woven into the fabric of who they are as a people.

Learn more about how NecroSearch International, and author Steve Jackson, got involved in the search for the Grand Duke Mikhail Alexandrovich Romanov in his book NO STONE UNTURNED.

Join our email list

Join our email list

Leave a Reply