At what point do we want law enforcement to spy on us and at what point do we want them to act?

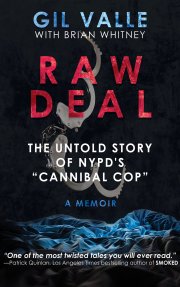

RAW DEAL: The Untold Story of NYPD’s “Cannibal Cop” is now available! Order your copy today!

When Gil Valle and Brian Whitney approached us about publishing RAW DEAL, we were told that Gil wanted to tell his story “his way.” Our concern was that “his way” included graphic descriptions of the sexual fantasies that landed Gil in hot water in the first place and included the abduction, torture and murder of women, as well as cannibalism. As with most of the general population, we find this sort of objectification and treatment of women, or any human beings, to be repugnant even as a “fantasy.”

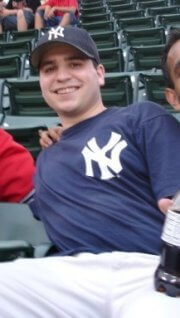

Gil Valle was just a “normal” guy–a police officer and a Yankee fan–until the FBI decided to arrest him for his thoughts.

However, we also note, that such fare constitutes a large portion of the content of many thrillers and mysteries both in print and as film—the dubious distinction being that those are works of “fiction.” But what then are one man’s online thoughts if he has not acted on them, except fiction? It can also be said that writers and readers of true crime, as well as those who work in the television and film industry that portray real crime and criminals, rely on this sort of content for their occupations and leisure time. As such, we feel that moralizing about Gil’s predilections to be somewhat duplicitous by anyone else who benefits from the depiction or description of criminal acts no matter how they attempt to couch it, or how “fictional” it might be.

Yet, we may have still hesitated to publish this story, except for one sentence the authors included in their proposal: “When, if

Author Brian Whitney helped Gil Valle tell his story “his way.”

ever, does ‘thought’ cross the line and become a crime?” How many of us have ever thought about, or considered, an action that if made a reality would constitute a crime? Now what would you say if for having had that thought, but never having acted on it, the FBI or some other law enforcement agency arrested you at gunpoint in your home in front of your neighbors? And as a result, you lost your job and friends, and that your life became fodder for sensationalized media reports that made you an international laughing stock? And that you were then prosecuted, convicted and sent to prison? For a thought, a fantasy, a fiction.

In the case of Gil Valle, if law enforcement truly believed that he or his online colleagues were going to actually act on their fantasies, why not stake them out, catch them committing a crime? Would they have arrested someone for “thinking about” robbing a bank who never acted on it? The fact of the matter is that Valle, and his online friends, as repugnant as their fantasies might be to the rest of us, they weren’t hurting anybody else. And yet even now, after having been exonerated of committing any crime, Valle continues to receive death threats and calls for his imprisonment.

In a free society that prides itself on the constitutional right to expression without government interference, “at what point does thought become a crime” is a serious question that goes beyond Gil Valle and his online fetishes. What about the person who belongs to online terrorist groups but never commits a violent act or breaks the law? Or uses the internet to look up how to make a bomb out of curiosity? What about authors of thrillers and mysteries who Google criminal acts to add realism to their stories? At what point do we want law enforcement to spy on us and at what point do we want them to act?

In a free society that prides itself on the constitutional right to expression without government interference, “at what point does thought become a crime” is a serious question that goes beyond Gil Valle and his online fetishes. What about the person who belongs to online terrorist groups but never commits a violent act or breaks the law? Or uses the internet to look up how to make a bomb out of curiosity? What about authors of thrillers and mysteries who Google criminal acts to add realism to their stories? At what point do we want law enforcement to spy on us and at what point do we want them to act?

When, if ever, does a “thought” cross the line and become a crime? It is worth thinking about, and so we bring you RAW DEAL: The Untold Story of NYPD’s “Cannibal Cop”

Join our email list

Join our email list

Leave a Reply