When I originally set out to write about the murders of Venus Montoya and Brandaline Rose DuVall more than twenty years ago, I had no idea the various paths the tale would take. I thought it was basically a story about the brutality and downfall of a small but violent Denver street gang, the Deuce-Seven Bloods.

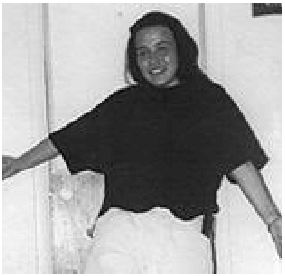

What made it different from other gang stories was that instead of shooting at rivals, some members had been accused of killing two innocent young women. One, Venus was in the wrong place at the wrong time when two members of the gang shot through a screen door into an apartment where they believed a police informant was visiting. The other, BrandI, just 14 years old, had no affiliation with gang members and was picked up at a bus stop and taken to a house to be raped, tortured and finally driven into the mountains and stabbed to death.

However, especially as the DuVall case unfolded and eventually wound its way into the courts, I became aware of a number of different threads that woven together made up the tapestry of a tragedy that affected so many lives.

The seeds for that story were sown when I noticed during one of the many pre-trial hearings a short, middle-aged woman who I was told was the mother Daniel Martinez, one of the defendants in the DuVall case and a founder of the Deuce-Seven. She looked frightened and lost and, most of all, alone.

I’d already met Brandi’s mother, Angela Metzger, who in addition to having lost her daughter in such a horrific way was dealing with a tremendous amount of guilt. Brandi had been making her way home from a friend’s house when spotted by gang members. Angela was already hearing the whispers and comments about “what kind of mother” would have allowed her child to be in such a precarious situation. Not that she needed any more vicious insinuations that what she was already heaping upon herself.

I could feel a mother’s heart breaking as she tried to negotiate all the conflicting emotions while try to prepare for the upcoming trials which would go on for eighteen grueling months. Trials at which she would be expected to testify at and not only identify her daughter’s effects, including a prayer card left at the murder scene, but what it had been like to see the body of her child on a cold steel table in a morgue. Wake up, baby, wake up!

However, Angela at least had the social workers in the victims assistance office of the district attorney. These professionals were there to help her get through the system, as shoulders to cry on when necessary, as well as run interference with the press, look out for her safety, and arrange grief counseling when needed. She was in good hands.

Yet, this other mother, who I identified in the book as Maria Simpson to preserve some of her privacy, had no one. She had purposefully asked her other son, Antonio, to stay away from the courthouse. He’d also belonged to the gang but left that night before Brandi arrived and was already breaking away from his brother and the other gang members. And while she knew the other defendants’ families, and was related or had been friends with them, the fallout had frayed those relationships, too.

I wondered what it was like to be a mother on that side of the aisle. Your son accused of a heinous murder. Knowing he might spend the rest of his life in prison or face the death penalty. While your other son grieved for the brother he did not save.

I gave her my business card and asked her to think about talking to me. She called soon after and said that she would agree to be interviewed.

We talked for the first time just before Christmas that year in the tiny living room of her rental home near downtown Denver. She was soft-spoken, reflective, often pausing as though listening to voices of regrets in her head. She was also deeply remorseful—not just by what her eldest son and his friends had done, but the role she’d played in her boys drifting into gang life and the predictably violent end.

If Brandi’s mom was haunted by guilt, the Martinez brothers’ mother was consumed by it. She talked openly about her own ties to gangs when she was young, her past addiction to drugs while her boys were growing up, and the bad choices she’d made, including leaving a second husband who’d been the role model they’d needed. But boredom and drugs had ended what might have changed the course of their lives, and Brandi’s.

Instead, she’d moved her sons back into the family home, which was in the middle of Denver’s gangland. And that’s where they’d joined the Bloods and earned their nicknames, “Bang” and “Boom,” the sound of guns.

Yet, she remembered them as little boys with sunny smiles, who loved their mother, their sister and each other. Danny was the outgoing one, who couldn’t wait to get outside in the morning to play. Antonio was more reserved and liked to draw. Then there was their best friend, Francisco “Pancho” Martinez, no relation but as close to her sons as a brother and a frequent visitor to her home when growing up.

It was hard for her to mesh in her mind those memories with the image of Danny and “Panch,” as she called him, with the monsters who’d committed unthinkable crimes against a child. And to understand that only by the grace of God did Antonio, who’d always been inseparable from the other two, have the sense to walk away that night.

Most of all when we talked, and in the many months of conversations that followed as the trial wound slowly towards their conclusions, I was struck by how desperately she wanted to talk to Angela and tell her how sorry she was. And that whatever happened to Danny, though she prayed it would not be the death penalty, she would accept it.

As a writer who’d reported on many murder trials and death penalty hearings, I’d written a lot about the ripple effect of violent crime beyond the immediate victims and perpetrators. Once the stone of something like a murder had been thrown in the pond, the waves moved out in ever-widening circles taking in more and more people, and sometimes entire communities.

The same thing applied in the murders of Venus, whose grandmother had raised her and was left to raise the dead girl’s young son, and Brandi, whose mother never got over her murder and remained a tormented soul before passing in 2008. The ripples had washed over them and gone onto extended families and friends, and people who read about what had happened. I cannot tell you how many times I’ve heard from a parent who said they were going to share the story of Brandi as a “warning” for their own daughters. A ripple of fear that still goes on to this day.

There were also the then-young district attorneys who prosecuted the cases, including four separate murder trials and two death penalty hearings. They’d had to read all the evidence, over and over until they knew every terrible moment by heart, seen the photographs of what had been done to two lovely young women. I know for a fact that they, too, despite many many trials, are still haunted by this one in particular.

Who we seldom think about being overwhelmed by those ripples are the many family members and friends of the half-dozen or so defendants. They weren’t present when Brandi was being raped, or tortured, or when she begged to be taken to a hospital and then for her life.

There were some who said vicious things from the spectator seats in the courtroom, or the halls of the courthouse—such as the victims “deserving” what they got. There’s a special place in hell for them.

Nor do I feel sorry for the defendants. Whatever traumatic events in their childhoods set them on a course towards rape, torture and murder are, perhaps, explanations. But they are not excuses; they do not forgive the crimes.

However, there were also mothers and fathers and siblings and many other family members, as well as friends, who quietly supported the accused who sat at the defense table. They listened to the horrors that the young men were charged with committing, sometimes weeping, or covering their faces; then huddled together in grief when the verdicts were announced, and the sentences handed down. But they did not all act out.

In a way that society rarely concedes, they were victims of their own loved ones, too. None of them had been there on that night. But no one outside of their circle cared. No one offered counseling. No one understood what it was like to still love someone who had done such horrible things.

More than twenty years later, I think about what became of all the players who took the stage for NO ANGELS. Some with major roles. Others just bit players. Victims. Heroes. Villains. Witnesses. And I think about all that wasted life and opportunity.

Brandy would be about 37 years old now. Maybe a mother. Somebody’s wife. Maybe not but those who loved her will never know. And maybe her mother, Angela, would have died at 51-years-old anyway, but she would have had her daughter another twenty-plus-years. Maybe held a grandchild.

Those young men who committed the crimes, were tried, convicted and sentenced, are middle-aged. Several will spend their lives in prison, never walking free, or taking a child to the park, or attending a graduation ceremony. They deserve being cast from the circle of humanity. Others, those who weren’t tried for murder but sexual assault, are out having spent their youth behind bars. They, too, reaped the seeds they’d sown.

Their children have grown up without them … all those birthday parties and Christmases and school plays they’ve missed. Spouses and girlfriends and friends have moved on. I read a blogpost that purported that Francisco Martinez had been badly beaten by rival gang members. Life in prison is a special kind of hell. But it’s better than what they gave Brandi DuVall and Venus Montoya, and those who loved those two young women, and better than what they did to their own loved ones.

The ripples caused by the stone of violent crime once thrown into the pond have no end.

Join our email list

Join our email list

I liked both the book and this follow up.

You know that you are still my favorite author and I am still your Slavedriver.!! LOL

Thanks for the certificate, I wrote a review on Amazon..