The tale I tell in “Mothers & Murderers,” has haunted me for almost forty years — and eluded me for nearly thirty.

I was first entangled with its characters in the summer of 1981. At the time, I was a cub reporter, covering a San Jose, California, trial involving the contract murder of a wealthy bachelor named Howard Witkin. Ten years later, after the murder investigation took an unexpected turn, I wrote a book proposal that promptly sold at auction to Simon & Schuster. It was going to be my second book, and I was sure it would be a piece of cake. It felt like one of those stories that would write itself.

Hahaha, ouch.

On leave from my job as the Mexico City bureau chief for the San Jose Mercury News, I traveled all over the United States. Cops and prosecutors and all sorts of other characters – including a psychic in Cupertino, California, and a lovesick FBI agent in Atlanta, Georgia – were eager to talk, with each of their stories more outrageous than the last. Arrest reports and steamy divorce court hearings provided a trove of useful details. A California prosecutor shared his files and even his diary with me in exchange for my promise that I wouldn’t hand in my manuscript until the murder story was resolved. No problem, I told him.

And yet it was.

That resolution took another four years. Simon & Schuster didn’t appreciate the delay. My editor, who’d bought the book, retired, and her replacement was less enthusiastic. More importantly, I was struggling, and failing, to write a good book. I couldn’t find my voice, nor could I even begin to effectively express why I’d become so obsessed with this story. Simon & Schuster finally canceled the contract. Thank heavens I didn’t have to pay them back for all the advance money I’d already spent.

Broke and blue, I put my files aside and again tried to focus on my day job as a foreign correspondent. By this time I was working as the Rio de Janeiro bureau chief for The Miami Herald. There were many exciting stories to cover – attempted coups, fugitive Nazis, military dictators being brought to justice — and I needed to prove myself to my new bosses. But the murder story still captivated me, so seven years later, after I returned to California on a journalism fellowship, I hauled out my old files again.

Over the next twenty years, I rewrote the book several more times. In 1999, I quit foreign reporting to freelance while raising my two sons. Whenever my paid work slowed down the murder story would once again consume me. I rewrote paragraphs in my head while swimming laps at our neighborhood pool.

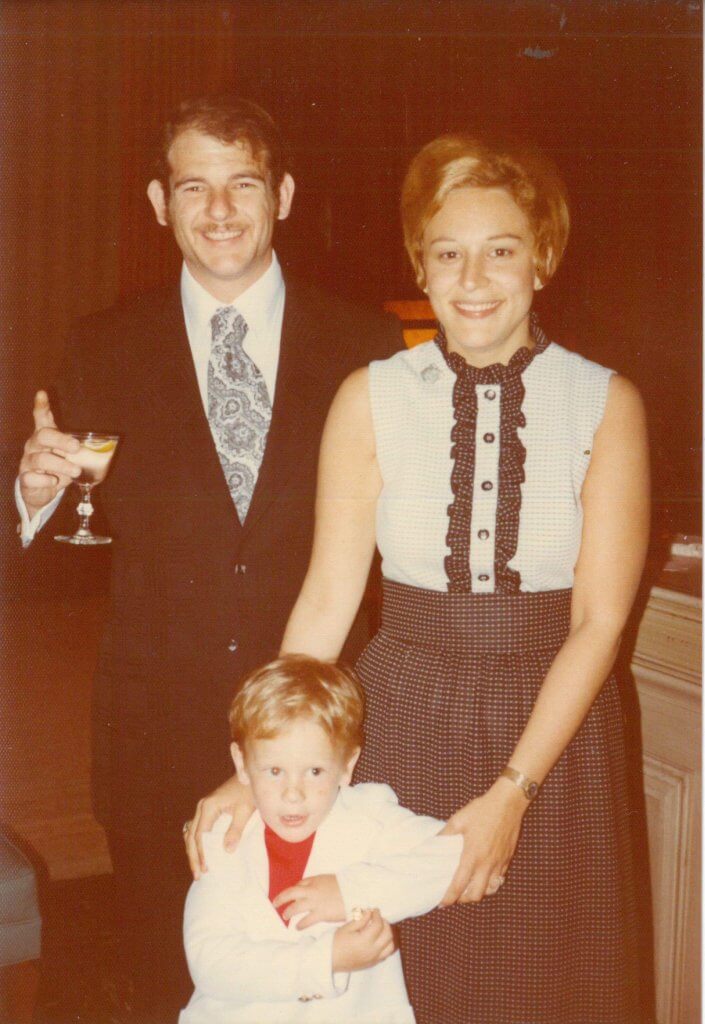

What intrigued me most of all was the mystery surrounding a woman who at first seemed like a sideshow to the murder: Judi Singer, Howard Witkin’s former wife. As I kept working, I realized my task was to peel back the many layers of secrets that surrounded her — and understand how they related to my own family’s enigmas.

Isn’t this, after all, what powers so many similar obsessions? These sorts of intimate questions make some stories so sticky that you can’t walk away. And it was only by writing, and rewriting and rewriting, and keeping Judi’s story in my head for all these years, that I eventually found some answers.

I feel obliged to note that I’ve done other things in the past 20 years, including authoring and co-authoring eight non-fiction books, writing newspaper and magazine stories, consulting, and raising those two sons. But all those other books really were pieces of cake compared to this one. This one was my Moby Dick.

In 2017, after another major rewrite, I found a well-connected agent who at least at first shared my obsession with Judi Singer. Alas, we also shared a mistaken belief that my manuscripts were ready before they really were. She sent them to all the top publishing houses. We had some breathlessly close calls. But no takers.

One year later, after yet another revision, we tried again. My agent liked my rewrite, but no one else did. She and I agreed it was time to part. I tried another agent. She couldn’t sell it either.

My mother passed away, and then my father. During their sad decline, I leaned on my husband and my best friend. I bought a second dog. I also joined two writers’ groups and returned to the psychiatrist I’d seen in the early 1980s to do the emotional work I couldn’t do while my parents were still alive. And I kept rewriting the damn book.

My parents’ departure removed a block I hadn’t known was there. I was writing better and more deeply, I knew, but I kept sending the manuscript out prematurely. It was rejected again and again, although the tone of the rejections changed. More editors were telling me they loved the book but for one reason or another couldn’t buy it. Memoirs weren’t selling like they used to. The sales team was being cautious. My last book hadn’t earned back its advance.

Around this time I started finding it harder to get new freelance gigs. My children had left home and I had more free time. All I could think of to do to fill that time while looking for paid work was to go back to the murder story. But rewriting was torture. I just wanted it done. Never mind that by now there was no doubt it wouldn’t unleash its hold on me until I got it right.

“Mistrust your sense of urgency,” my psychiatrist counseled. It was his mantra. I ordered a custom-made bumper sticker printed with his warning and pasted it over my desk.

My psychiatrist read my manuscript and told me he thought it was great, but I didn’t completely trust him. He told me I had trust issues. My best friend told me she loved the book and weirdly kept asking for more chapters to read, but I decided she must have poor taste. My husband sent me a cheery email, reminding me how an editor once rejected Herman Melville’s opus, complaining: “Does it have to be a whale?”

On weekends and some evenings when I didn’t have plans, I’d wander out to my converted garden toolshed to rewrite the first chapter, again and again. At times I was reminded of the scene in Stanley Kubrick’s “The Shining” where the terrified wife of the author Jack Torrance (played by Jack Nicholson) discovers what he’s been up to in the basement. Mainly, typing variations on “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.”

Throughout this time, I kept up the search for publishers, now trying smaller independent houses, without an agent. Once again, I had many close calls, but no cigar. Willing myself to get that “Shining” scene out of my head, I kept working and working on the manuscript until at last something shifted and I truly felt it was ready. Around this same time I was referred to WildBlue. They offered me a contract for the book within a week.

I’m so grateful to Steve Jackson and the rest of the team at WildBlue for appreciating this wild ride of a story, and I can’t wait to hear what our readers think. Drop me a line and let me know if anything in Judi’s story or my own obsessed you too.

Join our email list

Join our email list

Leave a Reply