When Governor Gavin Newsom issued an order to extend the moratorium on executions in California in March, the lead detective and the victims’ families in the Hawks case were all very upset.

After sitting through three trials in this case, two of which resulted in death sentences for defendants who killed their family members, they have been waiting a decade to see these murderers receive the ultimate punishment. But they are likely going to have to wait quite a while longer.

Even though voters have backed the death penalty in state referendums as recently as 2016, California has had a moratorium on executions since 2006. This is due to court challenges to the previous three-drug lethal injection protocol, in which one of the drugs was said to cause extreme pain, a violation of the U.S. Constitution protection against “cruel and unusual punishment.”

Newsom issued his reprieve just as the public approval process for a new protocol was about to end, saying that he couldn’t, in good conscience, carry out a capital punishment that killed even a small percentage of innocent people. He also dismantled the brand new, never-used death chamber that his Republican predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, built for $853,000.

Citing a National Academy of Sciences study, Newsom said that one in every twenty-five people executed in the United States, primarily men, is estimated to be innocent. He believed this finding gave him a moral imperative to act.

“If that’s the case, that means if we move forward executing 737 people in California, we will have executed roughly 30 people that are innocent,” he said. “I don’t know about you. I can’t sign my name to that. I can’t be party to that. I won’t be able to sleep at night.”

I’m not taking a position either way on the death penalty, because I believe it’s best for an investigative journalist and author like me to stay neutral on such topics. But I do want to state for the record that when I was still working as a daily newspaper reporter, covering jails and prisons for The San Diego Union-Tribune, I thought it was important to personally witness an execution.

I had to go to San Quentin twice for the same execution, returning some months later after the inmate received a last-minute stay. I got almost no sleep the night before my first trip, and I hardly slept the night I finally watched Tommy Thompson be executed in 1998. I stayed up writing my news story until 3 or 4 A.M., then got up early to interview the folks in the seats facing Thompson to find out what they witnessed. Standing off the side with the other media, I had a different, limited perspective.

Thompson went to his grave avowing his innocence. Years after he and his codefendant were tried and convicted, his codefendant said that he witnessed Thompson having what appeared to be consensual sex with a woman who was later found murdered. The special circumstance that made Thompson eligible for the death penalty was rape, and without that act to provide the motive for the murder of the young female victim, it’s possible that Thompson was telling the truth and only helped his buddy bury the woman’s body. Two jurors came forward once they learned this, and said they would have voted otherwise at trial if they’d known this before.

Given these facts, it was disturbing to watch him die, especially as he repeatedly pulled himself up off the table to mouth the words “I love you” to a woman in the stands, on the other side of the glass.

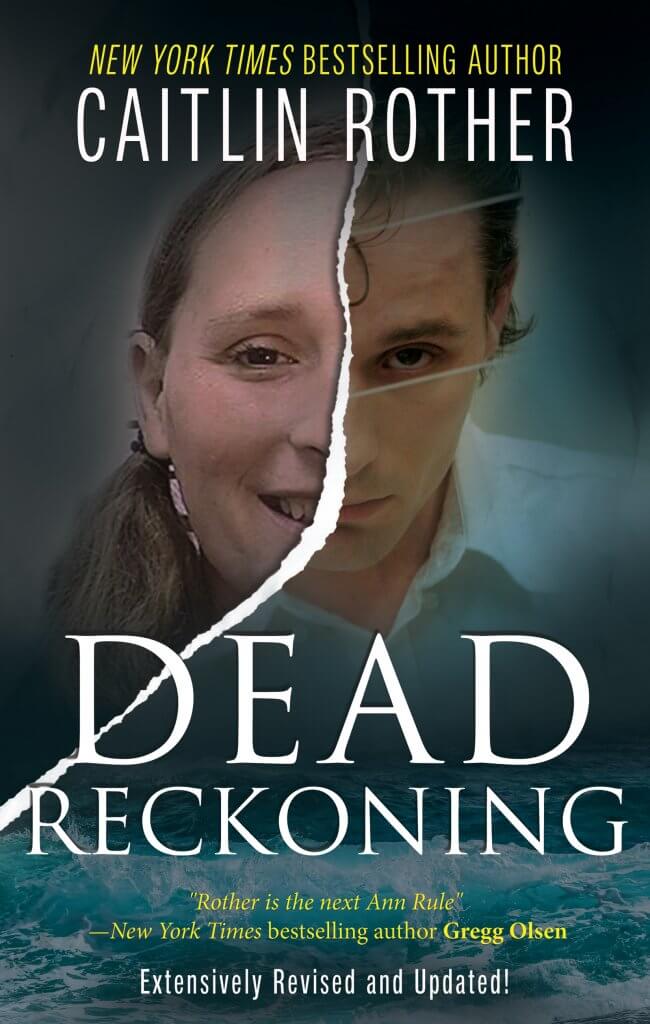

Now that I’m releasing an updated edition of my book, DEAD RECKONING, which features two convicted killers who are sitting on death row at San Quentin, I thought this was a good opportunity to explore national trends surrounding the issue of capital punishment.

On a state-by-state basis, the primary trend has been a downturn in the number of states supporting the death penalty. Within the past 15 years, eight states have abandoned the practice through legislation or the courts.

There also has been a decline in the number of actual executions, which are highly geographically concentrated in just five states: Texas leads the pack, with half of them occurring there. The others are Tennessee, Alabama, Florida and Georgia. Overall, the majority of the cases leading to executions are tried in only 2 percent of the nation’s counties.

California has the nation’s largest death row population—twice the size of Florida’s, which has the next largest. California has 710 men awaiting execution at San Quentin, and 24 women, who are housed at the California Central Women’s Facility in Chowchilla. This is the same prison where Skylar Deleon’s ex-wife and codefendant, Jennifer Henderson, was sentenced to serve a term of life without the possibility of parole.

Of the 135 death row inmates who have died in California since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976, only 13 of them have been executed; all the others died of suicide or natural causes.

Before Newsom made his move in March, six other governors had urged his predecessor, Jerry Brown, to roll back the death sentences of the 740 inmates living on death row at that time. But Brown refused.

Newsom clearly felt otherwise. Today, California is one of four states whose governors have issued moratoriums (the others are Pennsylvania, Colorado and Oregon), and one of 11 states that have the death penalty on the books, but haven’t used it in more than a decade.

Nationally, twenty-five states still have the death penalty, most of which are in the Midwest and South. The twenty-one that don’t have the death penalty are primarily in the Northwest, starting in North Dakota and moving east, (with the exception of New Mexico and Washington). The other four have moratoriums.

But until or unless the system is formally changed in California, prosecutors will continue to charge and try defendants in death penalty cases. “We’ve all arrived at the same conclusion,” San Mateo County prosecutor Steve Wagstaffe, the former president of the California District Attorneys Association, said in July. “We need to continue to do our jobs. The law is still on the books.”

That could change in light of Newsom’s reprieve. In July, the California Supreme Court weighed whether to “freeze” all death penalty trials. The argument was that juries couldn’t be expected to decide whether to recommend a death sentence if executions weren’t actually going to occur. That decision was pending when I wrote this blog.

Although for many the death penalty is a moral issue, it is also a financial and very political one. While some view it as a useful deterrent, others see it as part of a racially biased system that kills a disproportionate percentage of people of color, some of whom have been found to be innocent before and after they’ve been executed.

U.S. Attorney General William Barr recently took this issue in a new direction by ordering the federal government to restart executions after a new protocol is adopted, starting with five inmates already on federal death row. That may be more complicated than it might seem, because the protocol issue is what triggered California’s moratorium in 2006.

Sending someone to death row is quite a costly endeavor for taxpayers, because death penalty trials are often delayed and then are longer once they start. They involve more experts and witnesses, the defendant gets two attorneys vs. one (usually paid with tax dollars), and the trials have two phases vs. one.

On average, a death penalty trial generally costs twice as much as a murder trial without the special circumstance allegations that make the defendant eligible for the death penalty, the latter of which typically result in sentences of life without parole, known as LWOP. Similarly, the appeals for death cases are also longer and more involved, all because a person’s life hangs in the balance.

Those costs escalate when a system like California’s is broken, because prosecutors continue to charge and try defendants under the current system, even though the convicts will just sit in prison anyway—in single cells, with more security, and less yard time, making it more expensive to house them.

Even the Manson Family members, who were originally sent to death row, had their sentences commuted to life (with the possibility of parole) when the death penalty was found to be unconstitutional in 1972.

Charles Manson, viewed as the most notorious mass murderer of the 20th century, was technically eligible for parole but he stopped attending his own parole hearings, because he knew he’d never be released. He died at 83 of cancer and other natural causes in 2018. (For more information on that topic, you can read my book, HUNTING CHARLES MANSON, co-authored with Lis Wiehl.)

The information and statistics used in this blog came from the Pew Research Center, the American Bar Association, the National Death Penalty Archive, Phys.org, the Death Penalty Information Center, and various mainstream news stories.

You can order the book here: Amazon: wbp.bz/deadreckoninga

You can find out more about the book here: wbp.bz/deadreckoning

And you can learn more about me by visiting my website, https://caitlinrother.com. You can also find me on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Join our email list

Join our email list

Leave a Reply