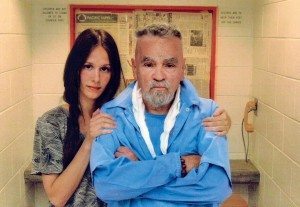

Even mass murderer Charles Manson couldn’t wrap his fevered brain around this macabre plot: His erstwhile fiancée had a bizarre scheme to put his corpse in a glass casket and get rich by charging admission.

Manson’s beloved, 27-year-old Afton Elaine Burton, wanted to marry the homicidal cult leader just so she’d own his remains when he died. A lot of people, she reckoned, would pay good money to see Manson’s preserved body in a modern-day, post-mortem peep show.

Manson, now 43 years into a life sentence in a California prison, bailed out of the engagement when he realized he’d been “played for a fool.” Plus, the 80-year-old killer—the chief bogeyman for three generations of Americans—believes he’s immortal, so it’s a moot point.

But who the hell would pay to see Manson’s corpse anyway? radio talk-show host Jack Riccardi asked this week.

Well, if history is any indicator, plenty of people would line up for a few seconds with Charlie’s carcass. And they’d happily pay for the E-ticket encounter.

We have a perverse fascination with bad men’s bones. It’s one part morbid curiosity, two parts schadenfreude, and a dash of celebrity worship. Somehow, our taboos about death don’t apply when it’s a criminal’s cadaver. The only thing more important to us than seeing justice done is seeing the proof (and maybe snapping a selfie with it).

In the Old West, outlaws’ corpses were commonly displayed publicly for days, mostly as a warning to anybody who might be considering a life of crime.

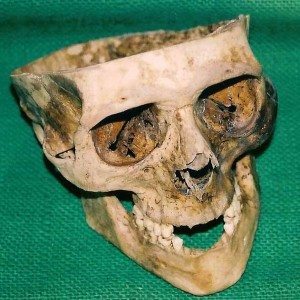

The uncapped skull of Wyoming outlaw Big Nose George Parrott. His skin became a pair of shoes and his skullcap a candy dish. (Ron Franscell photo)

Today, the most popular display at the local museum in Rawlins, Wyoming, is the skull of a murderous bandit named Big Nose George Parrott—and the pair of shoes a local doctor made from George’s skin after he was lynched from a downtown telegraph pole in 1878. Those shoes were a gift to the law-and-order governor of Wyoming, who reportedly wore them to his inauguration.

And in 1901, the menfolk of Clayton, New Mexico, posed proudly for a photographer with the corpse of famous outlaw Black Jack Ketchum, who literally lost his head when he was hanged. In those old photos, the men smile broadly as Black Jack’s head lies in the dirt at their feet.

More than 20,000 gawkers mobbed the Dallas mortuary where Bonnie and Clyde’s bullet-riddled bodies were displayed in 1934. They were cold-blooded killers (and bumbling robbers) but their romance fascinated otherwise law-abiding Depression-era Americans.

One of the strangest true stories of outlaw corpses begins in 1870, five years after the Lincoln assassination, when a young man named John St. Helen, fearing he was about to die, confided to his Texas lawyer that he was, in fact, the infamous assassin John Wilkes Booth.

To be sure, he bore a resemblance to the famed actor and dastardly killer. His age (about 40) was about right, and his theatrical demeanor gave one pause. And he told a remarkable story of mistaken identity on the Virginia farm where Booth was supposedly killed by federal troops.

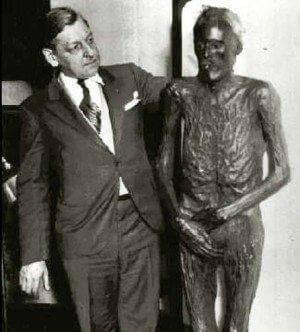

A mummy purported to be John Wilkes Booth traveled the American sideshow circuit for decades, well into the 1970s, before disappearing.

But St. Helen didn’t die. He recovered long enough to disappear again, reportedly leaving behind a pistol wrapped in a Washington newspaper dated April 15, 1865.

That was the last anyone heard of St. Helen — until 1903, when an itinerant housepainter named David George committed suicide in Enid, Oklahoma. He’d again confessed his “true” identity to a local widow, who described him as an intelligent man who often quoted Shakespeare when in his cups. And the coroner discovered George’s right leg had been broken just above the ankle years before, and he was born in the same year as Booth. They wondered, might David George’s alias be a combination of two Lincoln conspirators’ names, David Herold and George Atzerodt, both hanged for their roles in the assassination plot?

George/St. Helen/Booth’s corpse was mummified and displayed for two years in the front window of an Enid funeral home until his old lawyer came to identify George as his old friend, John St. Helen. He claimed the body, had it positively identified by Booth relatives, then sent it on a carnival sideshow tour as the mummy of John Wilkes Booth.

In 1937, the mummy reportedly attracted more than $100,000 from sideshow rubberneckers. Various carnivals displayed the mummy over the years until it vanished completely in the mid-1970s … about the time the feds were cracking down on displaying human remains.

Today, it’s one of the enduring mysteries of American crime: Where is the Booth Mummy?

Why do we care what became of Booth’s earthly remains? Why do people pay admission to see Big Nose George’s skull and loafers? Why are morgue shots of serial killer Ted Bundy a staple in true-crime chatrooms? And why did we want to see Osama’s corpse in all its grisly colors?

Maybe we want to reassure ourselves that our bogeymen are dead and no longer threaten us. That’s a good reason. Maybe we want proof they didn’t elude final justice. That’s a good reason, too.

Or maybe it’s just so we can snap a selfie with Charles Manson’s corpse and post it on Instagram, like a surreptitious snapshot of Jimmy Fallon in the men’s room at Applebee’s. Now that’s worth something.

In addition to his bestselling true-crime books, Ron Franscell is the author of “The Crime Buff’s Guides,” a fascinating state-by-state crime history series.

Join our email list

Join our email list

Leave a Reply