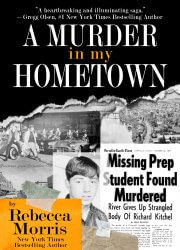

On a fall evening in Corvallis, Oregon in 1967, seventeen year old Dick Kitchel, a senior at the high school, disappeared after attending a party at the home of a couple in their twenties who often hosted gatherings and provided beer to a younger crowd.

On a fall evening in Corvallis, Oregon in 1967, seventeen year old Dick Kitchel, a senior at the high school, disappeared after attending a party at the home of a couple in their twenties who often hosted gatherings and provided beer to a younger crowd.

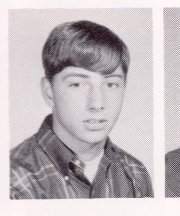

Dick was spoiling for a fight. He often had fights, but, surprisingly, he didn’t have enemies, or none that anyone knew of. Before his parents divorced, Dickie, as he was called in grade school, was a Cub Scout who loved summer baseball. Within a few years he seemed troubled, one of the kids who just wanted to get out of the house and couldn’t wait to get out of Corvallis. He took automotive and metal shop courses instead of college prep English and Math but was friends with almost everybody, those of us who were the children of college professors –Corvallis is home to Oregon State University – and others from farms south of town.

On the evening he vanished – Wednesday, October 11 – Dick didn’t have his 1955 blue Chevy station wagon, his one symbol of independence. He had cracked it up on Labor Day weekend in a spectacular drunk driving accident. A friend gave him a ride to the party. A scuffle took place. Dick was rude to the wife of the host, and someone grabbed Dick by the collar and held his slight body up against a porch pillar. There was, or wasn’t, a fist fight. Dick did, or didn’t, apologize. Later, while “The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson” played in the background,

a party-goer offered to give some of the boys a lift. Three boys piled into his two-toned early 1950s DeSota sedan. Dick was the last to be let out. The driver said Dick refused to tell him where he lived and got out of the car on a downtown street.

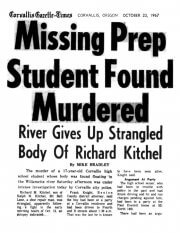

It was several days later before Dick’s father and step-mother reported him missing. Time passed and his body was finally spotted by two children as it floated down the Willamette River. He had been beaten and strangled. Like the Willamette, then the Pacific Northwest’s most polluted waterway, the investigation into his murder was murky and a tangle of obstacles. Police thought they knew who had killed Dick, but the D.A. was reluctant to take the case to a grand jury.

Author Rebecca Morris

Years passed. In 2011, a cold case detective concluded that he knew who committed the murder. Was it too late to find justice? Then he got word of the death of a major player in the story. Again, he wanted to take the case to a grand jury, but now there wasn’t the money or interest in closing a cold case with a suspect who was deceased. He left to join another police force in Oregon. But he did not forget the Kitchel murder.

Neither did the Corvallis High School class of 1968.

I attended junior high school and high school with Dick Kitchel and saw him evolve into what we called a “JD”– juvenile delinquent. As a veteran journalist and now an author, I realized I had never forgotten Dick. In 2015, I posted a short message on my high school class Facebook page reintroducing myself to those I had lost touch with. I explained that I was a writer and planned to look into Dick’s murder. I heard from dozens of classmates who said they had never forgotten him and the fact his murder was unsolved. More than forty-five years had passed but many still held strong opinions that his death was largely ignored by Corvallis police because

Dick was from the wrong side of the tracks. They believed if his parents had been prominent in the college town, and not working class, the case would have been solved.

Nearly 50 years later, I returned to my hometown to write about how the murder of a seventeen-year old boy changed a town, a school, and the lives of his friends.

“Crime writer Rebecca Morris revisits her childhood home only to discover that not only are residents still impacted by her classmate’s killing five decades earlier, but also the secrets her town holds. Thus begins Morris’s own heartfelt quest to unravel circumstances surrounding the cold-case investigation. A Murder in my Hometown is a must-read for both crime and memoir buffs.” –Cathy Scott, Los Angeles Times bestselling author of The Killing of Tupac Shakur and The Crime Book.

From The Book:

Ten days in one of America’s most polluted rivers, the Willamette, had not been kind to the body. The cold water had slowed decomposition, but the body was bloated, filthy and foul smelling. It was as contaminated as the water, sewage and tree limbs that kept it hidden and submerged until it moved free of a branch or the body’s gases caused it to float to the surface.

Dick Kitchel’s Class Photo

The body was taken by hearse to a funeral home. By the time it arrived, police suspected it could be that of a teenager who had been missing for ten days, seventeen-year old Dick Kitchel. His father and step-mother had initially shrugged off his disappearance.

Ralph and Sylvia Kitchel met two detectives, the assistant chief of police, the coroner and the state medical examiner at the funeral home. Showing little emotion, Ralph Kitchel identified the body. It was Dick, a sweet boy as a child. He’d outgrown Cub Scouts and had become one of the tough guys, a teenager known for his beer drinking and fist fights. Lots of fights, including ones with his dad.

The body had no identification or wallet. But it was Dick. He was dressed in jeans and a gray Oregon State University t-shirt. The only items in his pockets were two nickels, two pennies, a brass key, and a white handkerchief. Dick had died with his beloved Acme cowboy boots on.

Dick owned two other items that meant the world to him. One was his baby blue ’55 Chevy. The other was his Pacific Trail suede, sheep-lined jacket. He never went anywhere without the car and the coat. The car was history ever since he cracked it up Labor Day weekend. Where was his jacket, one of his parents asked?

Ralph Kitchel said, “Yes, that’s my son,” and he and Sylvia quickly left the room. The coroner and the medical examiner undressed Dick. He was small, only five feet two inches tall, 125 pounds. It hadn’t mattered when he played in the town’s Parks & Recreation summer baseball team in grade school. Everyone was small then. His light brown hair fell forward and swept to the right of his hazel eyes. They were shut now. While his friends had grown in height, Dick’s persistent small size caused some teasing and helped him form a hard shell. But despite his recent journey into fights and drinking, he was popular and his many friends still called him by his childhood name, Dickie. He was dating at least two girls, one a cheerleader. Now his life was over. No more speeding in his car or parties. No more evenings at Seaton’s, the most popular hamburger hangout for Corvallis teenagers who wanted to see and be seen. He was known as “the Mayor of Seaton’s” because of his frequent visits, notoriety, and reputation for both starting fights and breaking up fights between others.

There’d been a pretty good fight leading to his death. He had been beaten and there was a three inch wide bruise on his throat. The medical examiner concluded Dick had been strangled, but not with bare hands. Someone had used an arm or the sleeve of a coat.

There’d been a pretty good fight leading to his death. He had been beaten and there was a three inch wide bruise on his throat. The medical examiner concluded Dick had been strangled, but not with bare hands. Someone had used an arm or the sleeve of a coat.

The detectives learned Dick had been to a party the night he disappeared. They began to compile a list of names of Dick’s friends. One of them, or a family member, had most likely murdered the mayor of Seaton’s.

Join our email list

Join our email list

Fascinating and sad, very well written Rebecca. So sorry for the poor kid.

from a fellow Corvallisite.

This one looks really good too!

Looks as if this book would be a fascinating, spellbound read!

It really was a good read. I hope others check it out and comment. here.

The book brought back memories of Corvallis in the sixties. I graduated in 1969. I only knew Dick Kitchel in passing but have never forgotten his unsolved murder. Thank you for writing this book.