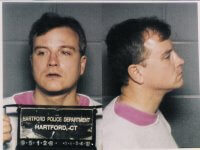

Serial killer Edwin ‘Ned’ Snelgrove once told a friend that he planned to be ‘Better Than Bundy.’

I am convinced that part of the “high” a serial killer gets from his murderous path of violence after he is arrested and facing the iron fist of justice is taking pleasure in the fact that he alone knows there are additional bodies (his victims) somewhere out in the world. What’s more, there is no doubt he will use those bodies as a bartering chip in dealing with law enforcement and/or the legal system when the time comes. Or, maybe the most obvious and honest answer, he will keep them for his own sick need of comfort while enjoying the pain those victims’ families go through not knowing.

There is also the strong possibility that he doesn’t recall killing certain victims and has forgotten about them. We like to think that serial killers in the real world are what we see on the big screen and television, yet it just doesn’t work that way in the reality of the situation. Not even close.

Take, for example, Chester Turner. Forty-four-year-old Turner, a self-professed pizza delivery man known later as “The Strangler,” was sentenced to death in 2014 for murdering ten women and an unborn fetus. Later, after he admitted to the fourteen, Turner was charged with murdering an additional four. (Another man, David Allen Jones, served eleven years for three of the murders until DNA exonerated him.)

Fourteen women and an unborn child. A one-man path of destruction. The cowardly work of a sadistic monster.

Then there’s former security guard Michael Hughes, who, in 1998, was convicted in South Los Angeles of killing four women, three of whom he choked to death and then dumped in alleys around Culver City. Hughes was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

Just recently, Los Angeles police cold case homicide detectives linked Hughes to the strangulation slayings of four additional victims: ages fifteen to thirty-six.

DNA caught Hughes this time.

And then, six days before Grim Sleeper serial killer Lonnie Franklin Jr. was due in court for a hearing, Los Angeles police detectives linked the former South Los Angeles car mechanic and alleged serial killer to three additional murders and one attempted murder.

These new bodies up the number of victims connected to Franklin to sixteen.

Sixteen human beings killed by one man.

But here’s the thing: We know there are more. Likely, in Franklin’s case, many more, in fact.

There always is.

Serial killer Edwin ‘Ned’ Snelgrove and author M. William Phelps bitterly clashed after Phelps revealed his true motives for interviewing Ned.

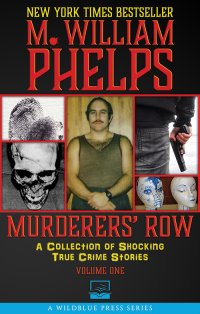

I reported and wrote about a similar type of killer in my book I’ll Be Watching You, which focuses on convicted serial killer Edwin “Ned” Snelgrove. Ned and I began a correspondence. He ended up hating me (this case is the focus of a story in my book MURDERERS’ ROW).

I have always believed Ned was responsible for many more murders and set out to prove my theory, which I ultimately did (to a small extent). But Ned’s case, as well as the others I mention here, bring up an important factor when studying serial murderers: their addiction to murder and how they feed that addition while locked up is an ongoing and unfolding area of study, an important part of the subtext of being a serial killer, which we need to look at closely if we are to understand how their minds truly work.

After being locked up, a serial’s mind does not stop obsessing or working in the same twisted manner it had while he was out killing. Let’s not kid ourselves into thinking that a few hours here and there with a psychologist every week, or some new medication, can suppress a lifelong desire and need to kill. There’s just no way.

I get asked at lectures and conferences all the time: Can we rehabilitate a serial killer in any way? Not a chance. Their minds are branded before they are born and their upbringing (and several other major factors) shapes them into the killers they become. I’ve simplified that argument here, but you get the picture.

A psychopath cannot change. A sociopath, well, maybe. It’s possible. But definitely not the psychopath.

Every time we see yet another serial arrested and brought in, believe that for every ten people he’s admitted to murdering there is one more out there he is keeping for himself to either barter with later on while behind bars (for whatever purpose he deems necessary at the time), or to just simply “get off” on while incarcerated.

For the serial, you bet your ass that while he is in prison, arms folded behind his head, lying in his bunk at night, staring at the ceiling, those other bodies he has out in the world give him a sick and twisted cheap thrill. Because in the reality of it all, that is how his mind functions. He cannot stop or control it.

For the serial, you bet your ass that while he is in prison, arms folded behind his head, lying in his bunk at night, staring at the ceiling, those other bodies he has out in the world give him a sick and twisted cheap thrill. Because in the reality of it all, that is how his mind functions. He cannot stop or control it.

M. William Phelps is the New York Times bestselling author of 33 nonfiction books, six of those about serial killers. His latest, Murderers’ Row, is available from WildBlue Press. In early 2017, look for Phelps’s next release, Don’t Tell a Soul; and, in August 2017, comes a project five years in the making, a true-crime memoir, Dangerous Ground: My Friendship with a SerialKiller.

Join our email list

Join our email list

Leave a Reply